The history of Haviland China is a remarkable tale of determination, ingenuity and devoted craftsmanship. While most people associate old Haviland porcelain with the French, in reality an American began the first Haviland china factory. David Haviland worked as a partner in the New York-based D.G. & D. Haviland Trading Co., an importer in English and French dinnerware, during the early to mid- 1800’s. One day a customer brought him a piece of china she wished to match, and the events that followed have become the legend of Haviland China.

It was only a broken teacup, but something about the quality of the porcelain struck Haviland with an insatiable curiosity about its origin. The fragile piece was remarkably white in color, almost translucent, and the consistency of the china itself was delicate and impermeable. Haviland knew this old porcelain must be French, but being a devoted dinnerware importer, he could not be satisfied until he had located the exact place in France where this impeccable china was manufactured.

After extensive travel through France, Haviland found the very factory that had produced the elusive teacup. It was located in Foecy, north of the region of Limoges. He special ordered several sets from this factory, suggesting particular designs to suit American tastes. However, the products he eventually received were not yet worthy of the name Haviland China.

Undeterred, David Haviland moved his family to Limoges, France in 1841 to begin his own factory. Limoges was already a leading center of pottery manufacturing, but he chose the region because it was then one of the few places in the world in which the natural clay ingredient needed to make china, “kaolin,” could be found. While similar materials could be found elsewhere, even in certain places in the United States, it was only the Limoges “kaolin” that, when fired, was capable of replicating the non-porous eggshell whiteware he had been seeking all along.

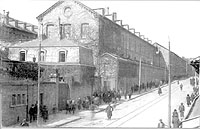

Haviland China distinguished itself immediately from the old French porcelain dinnerware when David Haviland refused to send his products to Paris for decoration, as was the standard practice. Instead, he set up a decorating studio within the factory, in order to produce patterns more closely suited to American tastes. This severely offended French sensibilities, which clung to old traditions about how porcelain should be manufactured. The idea was so radical, in fact, that protests by French artists were held outside the Haviland china factory during its early years. For a while, Haviland China was so controversial that many of the decorators producing American patterns in Limoges could not travel alone at night!

Eventually, however, Haviland China came to be respected by French society. Far from remaining isolated from artistic developments in the country, early Haviland China was strongly influenced by the Impressionist movement that developed in France during the same period. In 1872, David’s son Charles opened the Auteuil Studio in Paris. It was here that the famous “Haviland Barbotine” was first produced. This innovation of painting on earthenware with liquid clay attracted the attention of great French artists such as Manet, Monet, and the Damousse brothers. It is often said that the work of the Impressionists greatly influenced the floral designs of Haviland China.

After David Haviland’s death in 1879, the firm passed into the hands of his two sons, Theodore Haviland and Charles Edward Haviland. However, an irreconcilable disagreement concerning business practices led to the liquidation of the old porcelain factory, and the creation of two separate Haviland china companies. Charles Edward began “Haviland et Cie,” French for “Haviland & Co.,” whileTheodore Haviland installed another porcelain producing factory under his own name. Charles Haviland marketed his china under the slogan “Buy Genuine Haviland,” while Theodore Haviland commissioned several artists from the Auteuil Studio to work for his firm, “Theodore Haviland, Limoges.” While the rivalry seemed vital at the time, ultimately the work of both of these companies would become synonymous with the name Haviland China.

During this time, as though seeking to escape the French porcelain rivalry, Charles Haviland’s son Jean moved to Bavaria in 1907 to begin the Johann Haviland Company. Bavaria was the only other region outside France and China where the essential “kaolin” could be found. The Johann Haviland Company was comparatively short-lived, ceasing production in 1924. The name rights to Johann Haviland were eventually purchased by an Italian Company, and later by the Rosenthal Group.

Although Haviland & Co. continued to operate, the future of the company seemed dire following Charles Haviland’s death in 1921. Theodore Haviland’s superior marketing strategies allowed his company to survive the Stock Market Crash of 1929, which finished Charles’s company for good. In 1941, Theodore Haviland, Limoges, under the ownership of Theodore Haviland’s son William, won exclusive rights to Haviland & Co.’s name and backstamps. The two Haviland China companies again became one.

It is estimated that over 60,000 Haviland China patterns were produced by the time the Haviland family retired from management in 1972. The pieces that remain are highly collectible, not only due to their historical and artistic significance, but also because of their sheer beauty and timeless quality. The name Haviland China today is inseparable from the legacy of French and American dinnerware, and are certain to be collected and treasured for many years to come